Has this ever happened to you? You are reading something in Chinese and then come across a character you don’t know. You pull out your phone and open your Chinese dictionary app to look up the character. You find the definition, understand what it means and then move on. No more than 10 seconds later, you run across the very same character and you’ve totally forgot how to say it or what it means.

Why do we forget?

There are many reasons we forget things. One of the most common reasons is because we are focusing on understanding or doing something, not remembering it. I think we have all walked into a room to do something and forgot the reason we came in. It starts when we decided to go to the room with a specific action in mind, intending to accomplish a task. We are focused on completing that action, not remembering what it is, thus it is easy to forget why we walked into the room in the first place.

This same problem is found when we are learning new words in a foreign language. Sometimes we are focused on understanding the word and miss out on actually remembering it. The scenario shared at the beginning of this article is a prime example. You are reading with the goal to understand what you are reading. An unknown character is an obstacle to your goal so you look it up to understand what it means. After you understand it’s meaning, you move on without having tried to remember it, and when you run across it 10 seconds later, you’ve totally forgotten what it means. You are more focused on comprehending the sentence (a goal or result) than in remembering the character (a task).You’ve proverbially walked into the room and forgotten why you came in.

Reading Pain vs. Extensive Reading

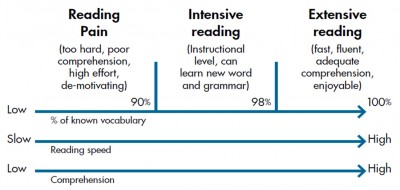

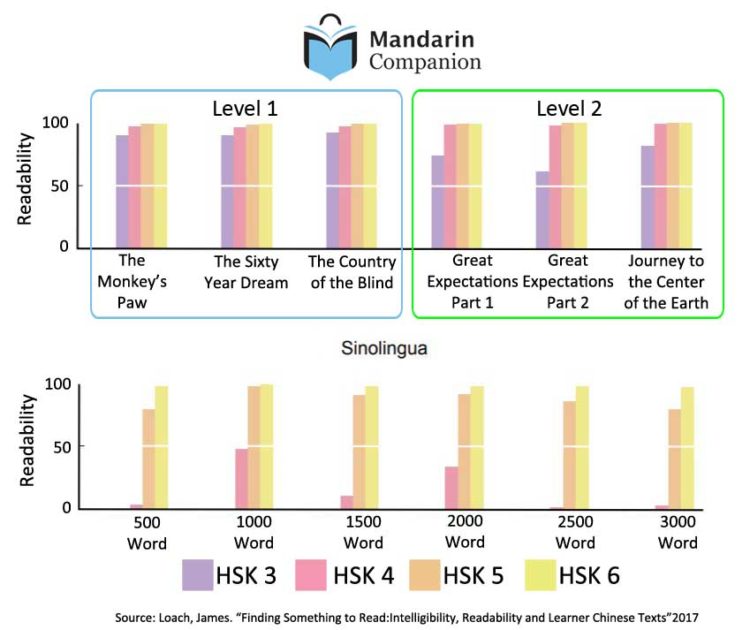

This helps us to understand why reading below 90% comprehension, or reading pain, is less effective for learning. If we are using all of our mental effort just to comprehend what we are reading, it is difficult to devote sufficient focus and mental power on remembering the words and characters that are new to us.

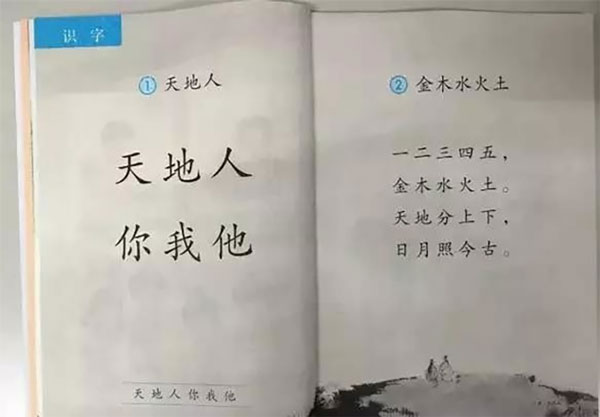

Conversely, this also illustrates why reading at high levels of comprehension, 98% for an extensive reading level, is very effective for learning new characters. If we can already understand and comprehend what we are reading, it is much easier to devote the mental focus and power towards remembering a new word or character, especially when supported by context.

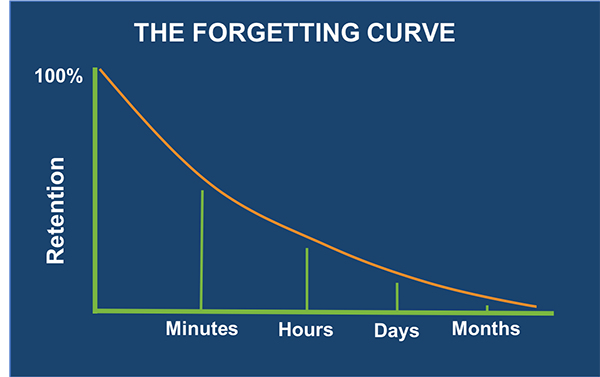

The Forgetting Curve

Even when we devote specific focus and memory muscle towards remembering a word, it is still easy to forget. This is in part because we are constantly fighting against the “forgetting curve”, a concept that simply states we forget things over time if there is no attempt to retain it in our memory. Studies show that we forget over 50% of what we had learned within less than 24 hours! A week later we may remember only 20% and a month later that can drop down to about 10%.

Whenever we are trying to learn something, we are constantly fighting against the forgetting curve. Things we have just learned are fragile and easy to forget.

How to Commit Learning to Memory

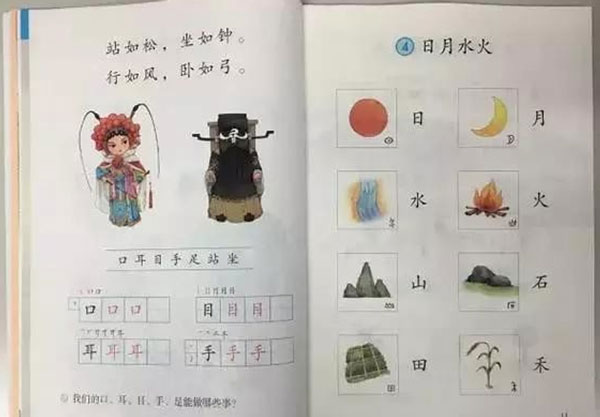

Research in the area of language learning has shown that it takes 10-30 or even 50 or more meetings of an average word before it is truly learned, and that is for an average word. When facing words that are abstract in meaning or use, much more repetition may be required before they are retained in our memory.

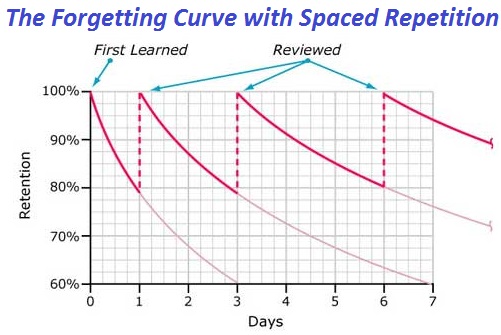

But we do not learn things well all at once. It is not enough to repeat a new word 50 times in one cram session. There must be repetition, but it must be spaced out over time also known as “spaced repetition”. It is better to see the same word 10 times a day over 5 days than it is to see the same word 50 times in one day. Using the concept of spaced repetition is highly effective in helping us to commit new words to memory. This is why text books offer sections to review what has been learned.

Today there are many apps and flashcard programs available that use spaced repetition algorithms to recycle characters at optimum times designed to maximize memorization and retention of new and recently learned words. All of these are great uses of technology to fight against the forgetting curve.

Not all Forgetting is Bad

There are advantages to forgetting some things such as outdated information, where you parked your car yesterday, an old password you no longer use, the chores your mother asked you to do (this is a bad long term strategy; don’t do this), or even the details of a former long-term relationship. This type of forgetting can even help your memory as you prune away irrelevant events and are better able to remember more important details, a phenomenon known as “adaptive forgetting”.

In fact, in learning a second language, forgetting can help you learn! It has shown that suppressing your memory of your native language can be helpful when learning a second language. Many learners do this in class rooms where they focus on speaking only Chinese. Often there is an urge to speak in English, but the learner consciously focuses on speaking Chinese instead.

How to Not Forget

If we want to not forget what we have learned, we must have many opportunities to encounter newly learned words over an extended period of time if we are to retain it in our memory. If there are not enough opportunities, then the chance that a word will be forgotten increases exponentially as time goes on. An axiom states “The most important thing to study is what you learned yesterday.”

Extensive reading is a highly effective way to not-forget words you have learned. It provides an ideal environment for remembering because the learner will be reading at a high level of comprehension thereby freeing up mental power that can be used to remember new words AND because it provides spaced repetition through continuous recycling of the same words in context. This is precisely the experience of the following reader.

“There is a lot of repetition in the descriptions—certain words and grammatical structures are used over and over—for the language learner, this is a good thing. In the end, I not only improved my ability to recognize high-frequency characters, but I’ve also picked up vocabulary and grammar along the way.”

– Peter S.

Even with all of this, sometimes you’ll still forget, and that’s ok! Forgetting is natural. If we forget something, it doesn’t make us dumb, it makes us human.