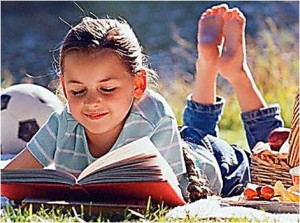

Reading makes you smarter. A study by the UK’s Institute of Education tracked a group of 6,000 British citizens over the last 40 years since the day they were born. This is one of the first studies of its kind that examines the effect of reading for pleasure on cognitive development over a long period of time. There are some very compelling findings that have implications for learning any language.

Finding: “Reading for Pleasure” is important

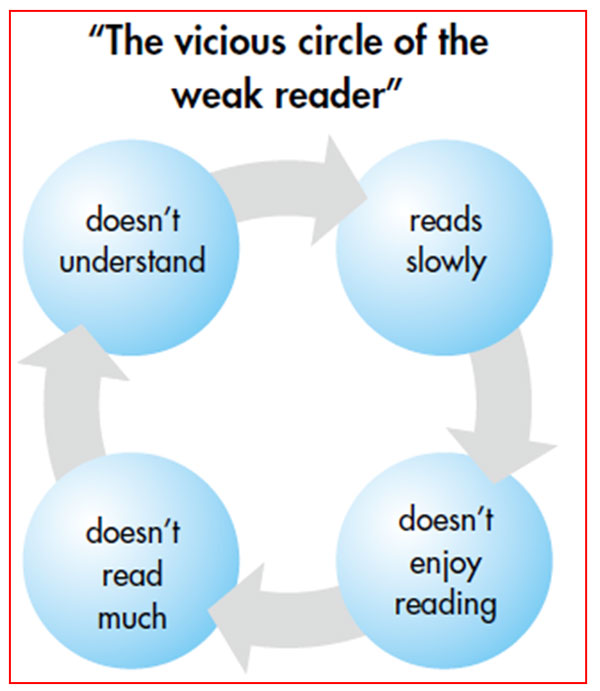

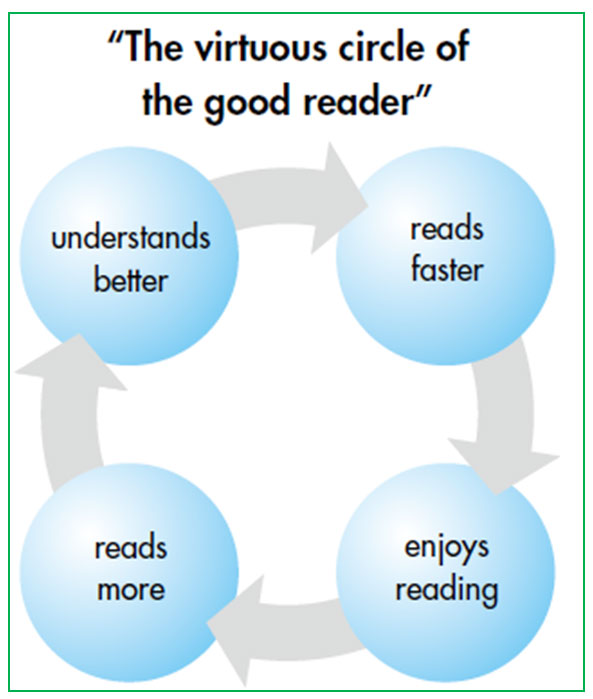

This is not assigned reading, forced reading, intensive reading, or reading pain, it’s reading for fun. This implies reading at an extensive level (~95-100% comprehension) as it is unlikely that stopping every few words to look up a new word can be considered “pleasurable”. This very concept is a key idea proposed by Dr. Steven Krashen and his famous “Input Hypothesis” of which most of today’s language education is based. He goes a bit further stating that “compelling” (not just interesting) reading is essential for true language acquisition. It would make sense that reading for pleasure can have a cascading positive effect on learning a language.

Finding: “Reading for pleasure had the strongest effect on children’s vocabulary development”

Experts and academics have been saying this for years: Reading is the most powerful way to develop your vocabulary. Flashcards and textbooks are excellent at introducing the language, but developing vocabulary and building fluency requires much more that reading provides.

Finding: “They discovered that [children] who read books often…gained higher results in all three tests (spelling, vocabulary, math) than those who read less regularly.”

This phenomenon has been experienced by learners of many different languages and is not exclusive to kids. For example, I once worked with a Chinese student named Bobby who used extensive reading to improve his English. About 6 months before taking the SAT, he started reading a lot of books. He found that his scores on practice tests improved significantly. Why? He was able to read the question quicker, understand it quicker, read the answers quicker, think about it in English quicker, and more quickly provide a response. He went from having a hard time completing the test in the time allotted to having extra time left to go back and review his answers.

As for reading improving math scores, Dr. Alice Sullivan who conducted the study said “It may seem surprising that reading for pleasure would help to improve children’s math scores,” she said “but it is likely that strong reading ability will enable children to absorb and understand new information and affect their attainment in all subjects.”

While it may not be determined the exact reasons test scores improve due to reading, the fact that they do improve is clear. The next time you hear somebody say “I don’t have time to read, I need to study”, you’ll know what to say!

Profound Insight

While the results seem rather straightforward, looking at the data from a different angle reveals a profound insight. We know that the 6,000 people in the study live in a native English speaking environment (the UK) and it would be safe to assume that each person has been listening and speaking English every day, however those who frequently read for pleasure performed better on tests. This points to a profound insight:

Reading develops your language in ways that listening and speaking cannot.

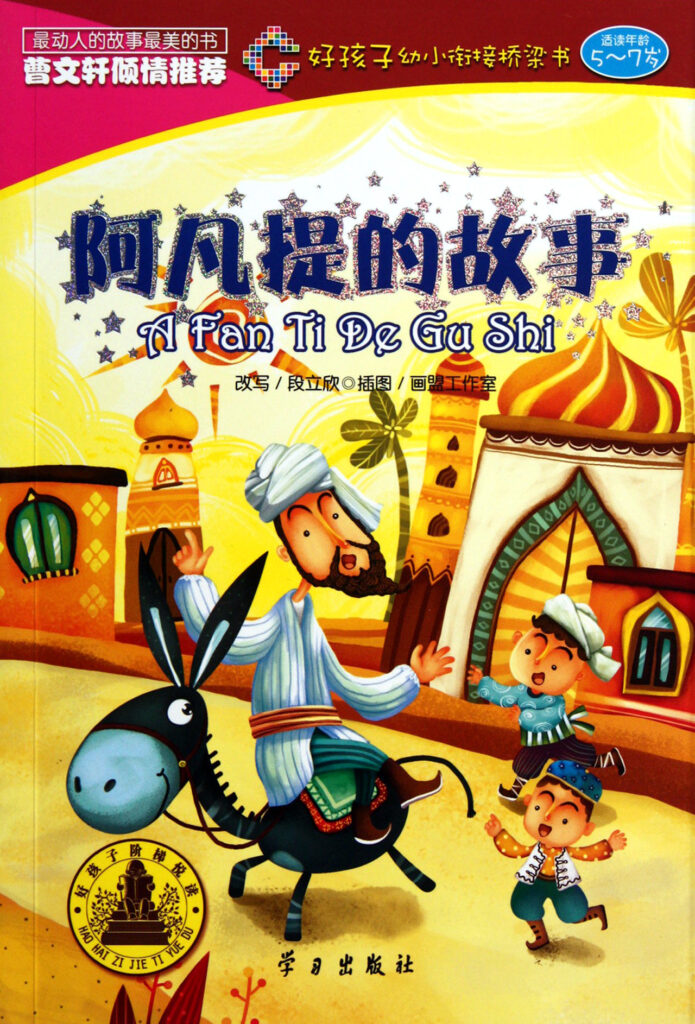

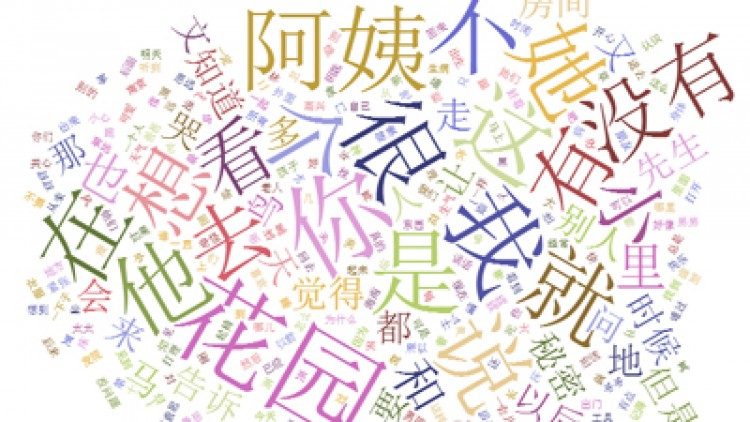

This means focusing solely on grammar or vocabulary (or even the dreaded HSK) while neglecting to READ meaningful Chinese will actually inhibit your overall language development. Likewise, knowing lists of characters but not reading in Chinese will limit your progress as well.

Solution: Read! And while you’re at it, read something you’ll enjoy!