Karaoke–or KTV as it’s known in China–is an exceptional way to improve your Mandarin. If you won’t take that as the gospel truth, then do I have an article recommendation for you. But even if you agree wholeheartedly, you’re left with a serious problem. What are the songs you can actually sing?

Finding an appropriate one for your level is easily the biggest hurdle, so we put together a list to help you out. These are our top 5 favorite Karaoke songs for learning Mandarin–sorted by level to find the best match for your abilities.

We dug deep to give you a feel of each song before you listen, provide context and background on the artists who made them, and most importantly, give you some juicy data on the actual Chinese you’ll need to learn.

Below each song is a table showing how many characters there are in total, the number of unique characters, and a breakdown of each by HSK level. We’ve also included our take on whether it’s an entry level, beginner, or intermediate challenge!

1. I Want Your Love—Grace Chang

我要你的爱 (Wǒ yào nǐ de ài)

This classic, most famously sung by Hong Kong actress and singer Grace Chang, was re-popularized in the 2002 blockbuster Crazy Rich Asians. Solidly in the genre of old school swing, the song has nevertheless been remixed and re-sung several times in more modern genres.

The big band energy and lively tempo makes for one heck of an earworm. Nevertheless, it’s a fantastic song for entry level Chinese students, as the Mandarin is short and sweet. In fact, the hardest part by far is the English!

In case you thought I was exaggerating; you’ll be happy to know there are only 10 unique Chinese characters in the entire song. All but two are in the HSK 1 vocabulary list, and the missing duo, 要 and 为, are so common you’re likely to have already encountered them well before reaching the HSK 2 level.

If you are just beginning your Mandarin journey, this is the song for you.

Character Count

Total: 101 | HSK 1: 76 | HSK 2: 25 | HSK 3: 0 | HSK 4+: 0

Unique: 12 | HSK 1: 10 | HSK 2: 2 | HSK 3: 0 | HSK 4+: 0

2. The Moon Represents My Heart—Teresa Tang

月亮代表我的心 (Yuèliàng dàibiǎo wǒ de xīn)

Teresa Tang is synonymous with Chinese Karaoke. And that’s barely hyperbole. You do not go out for KTV in the Mandarin-speaking world without hearing a rendition of at least one of her songs, and the “Moon Represents My Heart” is no exception.

Originally sung by Chen Fen-Lan, Tang’s 1977 rendition practically introduced pop music to China. It found a place in the hearts of people all over the country and simply never left.

While living in China myself, I must have heard the song half a dozen times before even knowing what it was called. Naturally wanting to identify it, I hummed the tune to a work friend. Before he had a chance to respond with a name, every single one of our local coworkers within earshot spontaneously picked up the song in the same place with nothing short of joy in their eyes.

With 82.5% of the characters in HSK 3 or below, I’d recommend this for higher level beginner or lower intermediate Mandarin learners. The total number of characters is also quite low, making it an easier song to get a handle on. And if you ever go to China and try the Karaoke, this is the song to sing. They’ll love it.

Character Count

Total: 193 | HSK 1: 136 | HSK 2: 18 | HSK 3: 16 | HSK 4+: 23

Unique: 40 | HSK 1: 20 | HSK 2: 8 | HSK 3: 5 | HSK 4+: 7

3 I’m a Girl—Yuki Hsu

我是女生 (Wǒ shì nǚshēng)

Straight off Yuki Hsu’s first album, “I’m a Girl” should have been lost to the many catchy hits that the turn-of-the-millennium singer’s talent produced. That better future never came to be, however, as her career ended abruptly a mere three years later in 2003, only for the artist’s star to flare once more in 2007 with her final album, Bad Girl.

“I’m Girl” is representative of the upbeat optimism and quirky relatability of Hsu’s early discography, standing in stark contrast with the tragic trajectory of her career as a whole. English-language sources on the story are scarce, describing allegations of breach of contract and blackballing, legal action, and financial ruin.

Delving into the details would likely require using Mandarin to read the original news articles or better yet finding Mandarin forums or blogs examining the topic.

Fortunately, learning this wonderful song requires far less Mandarin skill and time invested than the story behind it. The chorus is catchy and easily memorized and the rest of the lyrics repeat multiple times throughout the song. That said, there are a large portion of HSK 3 and above characters.

This song is great for intermediate learners.

Character Count

Total: 331 | HSK 1: 208 | HSK 2: 42 | HSK 3: 34 | HSK 4+: 47

Unique: 67 | HSK 1: 30 | HSK 2: 8 | HSK 3: 13 | HSK 4+: 16

4 Look Over Here, Girl—Richie Ren

对面的女孩看过来 (Duì miàn de nǚ hái kàn guò lái)

You couldn’t ask for a better song if you’re as much an aspiring guitarist as you are an aspiring Mandarin speaker. Released in 2002, Richie Ren’s cover of “Girl, Look Over Here” is mellow yet energetic and reminiscent of the works of Western bands like the Head and the Heart.

Another artist from Taiwan, Ren’s music career had the rather humble origins of working in a store that sold musical instruments. During this time, he was also practicing guitar, an instrument that would become a defining characteristic of his musical career.

The song itself is about a lonely guy trying, and seemingly failing, to catch the attention of a girl he likes—or any girl, for that matter. The chorus and refrain are catchy, relatively simple, and easily memorized, but there’s definitely some higher level language throughout the song.

With the high proportion of HSK 3 and higher characters, this is ideal for intermediate and upper intermediate Chinese speakers.

Character Count

Total: 323 | HSK 1: 178 | HSK 2: 61 | HSK 3: 32 | HSK 4+: 52

Unique: 103 | HSK 1: 37 | HSK 2: 20 | HSK 3: 16 | HSK 4+: 30

5 Chengdu—Zhao Lei

成都 (Chéng dū)

Released in 2016 by Chinese singer-songwriter Zhao Lei, “Chengdu” is a heart-wrenchingly beautiful song that proved a hit both within and beyond the artist’ home country. Its lyrics are as much a tribute to the Chinese city of Chengdu as it is a tribute to romantic nostalgia and longing.

Like much of Zhao’s music, this original may draw on the artist’s personal experience. Before his career truly took off, Zhao took to the roads and traveled his country as a wandering musician. It wasn’t long until he was performing at festivals and national tours. He even participated in China’s Singer, a renowned competitive music show, and performed “Chengdu” to the delight of the audience.

The lyrics are a bit more complex than some of the other songs on this list, with more advanced vocabulary and sentence structures. However, the song’s slow and melodic pace makes it easy to follow along.

Upper intermediate and advanced speakers will do best with this song.

Character Count

Total: 395 | HSK 1: 158 | HSK 2: 73 | HSK 3: 70 | HSK 4+: 94

Unique: 102 | HSK 1: 25 | HSK 2: 19 | HSK 3: 19 | HSK 4+: 39

No matter whether you’ve set your sights on Grace Chang’s “I Want Your Love” or rise to the challenge of Zhao Lei’s “Chengdu,” you’ve set yourself up to do something pretty darn special. You’re learning Mandarin Karaoke. (Or Mandarin KTV if you’re feeling cultured!) This is an opportunity to take a swan dive into real Chinese culture as it exists today, not to mention an incredible way to polish your fluency. So, get some practice and go out there and sing.

If you have a favorite song for KTV, let us know in the comments!

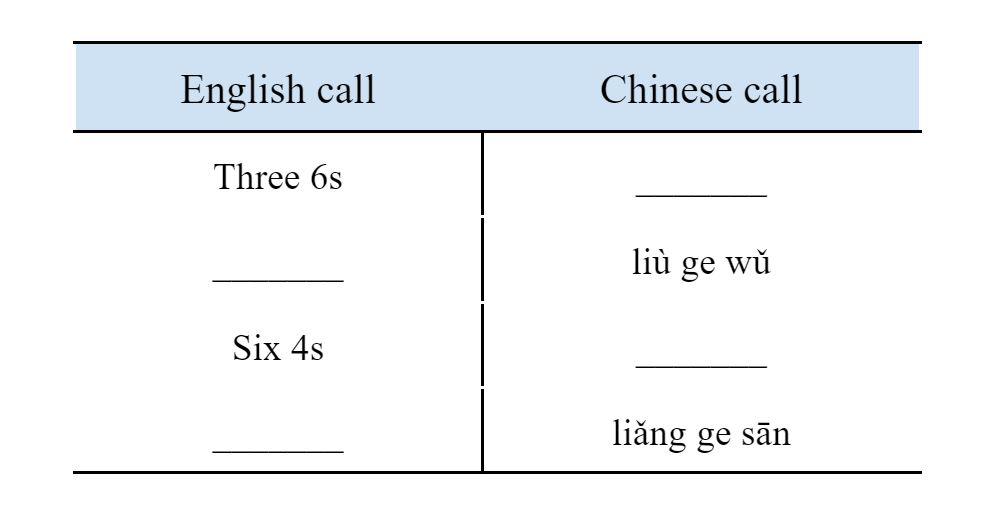

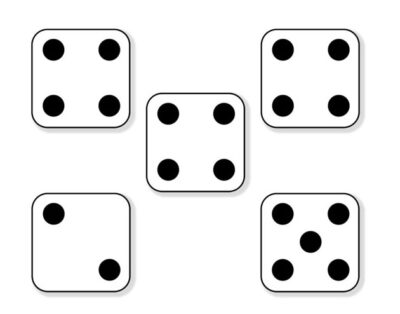

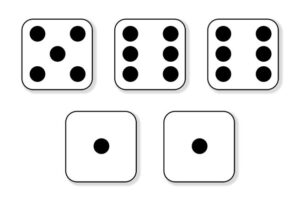

Basic play

Basic play Making a Call

Making a Call

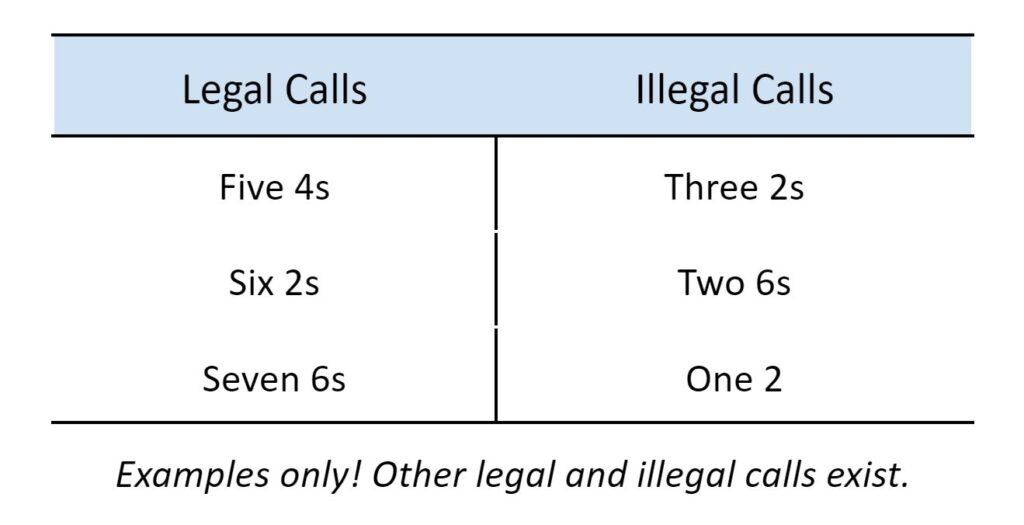

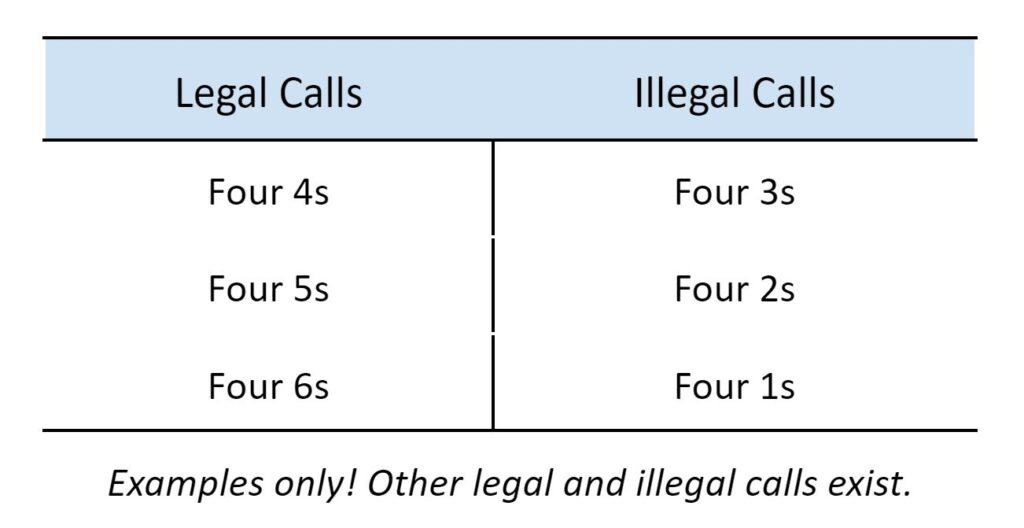

Legal Calls and Illegal calls

Legal Calls and Illegal calls

Calling a Bluff

Calling a Bluff Ending a round, beginning the next

Ending a round, beginning the next Using Chinese to Play!

Using Chinese to Play!