Guest post by Diane Neubauer

You are learning Chinese and want to read too. Great! I am going to share some ideas to help you make your reading experience more pleasant and productive. Yes, even if you only know 100 or 50, or yes, dare I say as little as 10 characters, there are ways to read very simply in Chinese and even apply extensive reading at the true beginner levels.

Reading Chinese, in a lot of ways, can feel like starting all over, even if you can understand spoken Chinese well. But reading in Chinese is awesome; it feels like taking Chinese from black-and-white to vivid color. Being able to connect the written with the spoken language has been a rewarding experience that seems to deepen my understanding of the logic of the Chinese language and how concepts overlap in different words. Being able to use Chinese in text messages with friends, comments online, or even reading subtitles on a favorite show is worth it.

When I say “read”, I do not mean merely recognizing words in isolation, or being able to memorize characters or their components. Those are great skills. However, I’ve seen students ( myself included) work hard to memorize individual characters or words in isolation and still struggle to understand sentences and paragraphs, even when they contain familiar words. When I use the word “read”, I mean understanding texts that are sentence-long, paragraph-long, and multi-paragraph-long. If you too wish to learn to read Chinese like this, then read on!

How I Learned Chinese

I have taught Mandarin Chinese in elementary, middle, and high schools since 2007, however I didn’t grow up speaking Chinese. I was born in the USA in an English-speaking home. I didn’t begin studying Chinese until I was 19 and since that time I’ve seen a significant amount of change in the way Chinese is being taught and learned.

My college Chinese classes were fairly typical: we recited vocabulary, studied grammar, practiced handwriting, focused on pronunciation, and translated texts. I worked with flashcards to practice vocabulary, and when reading, I slowly pieced together the meaning one word at a time. Reading material, which came from our textbook, included short conversations with plenty of new words that were used once or twice each. Occasionally we would read a short story about a chengyu (4-character-long sayings often referring to legends or historical events). If you wanted to read something, you had to translate it if you really wanted to understand the message and I found it took a lot of work to think in Chinese. However, the program and my professor were very highly regarded and I was committed to working hard.

After college, I studied and worked in China for nearly four years. I had three semesters of one-on-one classes at a university. My instructors did use a textbook, but there was less focus on it. Instead, my favorite teacher would draw on words from a vocabulary list as we would talk about our life experiences. There was more emphasis on understanding my teacher and what we read together than producing new words and sentence patterns. My teachers would rephrase and expand on what I said so I heard native Chinese examples of what I intended to say, rather than make me rehearse sentences that weren’t my own. As result there was more of a back-and-forth discussion at my level of comprehension.

Teaching Career

After I moved back in the US in 2004, I started tutoring in Chinese and then in 2007 began teaching Mandarin Chinese in a school. At that time, there were few textbooks (mainly those designed for college students) and fewer learner resources online. I was teaching 10-year-old beginners, so I went back to what I knew: teaching a mix of vocabulary, grammar, handwriting, and pronunciation combined with dialogue and games in attempt to make class time for fun. However, I wasn’t seeing the progress I believed was possible which set me on a professional quest to find a better way.

Today there is more interesting content for beginners, like story books and video series. There are also excellent podcasts, apps, and games available. But what if materials promoted as “beginning level” are really a struggle? As noted in articles in this blog and other sites about learning Chinese, reading that is too difficult is not only demotivating and time consuming, it pays off less in terms of your development of reading skills.

So what should you do? Do you just need to buckle down, work on memorizing characters, and wait for a payoff months or years into the future when you can read something enjoyable? Are there any alternatives to memorizing lists of characters and words so you can hope someday to read something in Chinese?

What I’m about to share with you is drawn from 10 years of learning, research, and experimenting along with students over the years. My students have helped me to work out how reading Chinese can work, even from the first week of classes.

1. Focus on Listening Comprehension

At the beginning, focus on listening comprehension for perhaps a few days or weeks, depending on how much time you have for learning and how soon you want to read. It is very helpful to first have a good 语感, the Chinese word for “language feel”, which several studies call “mental representation”. This can significantly help when you read Chinese because your brain will have a better sense at what “sounds right”. Having this feel for the language reduces the cognitive load, or the amount your brain is required to work, thereby freeing up more mental space allowing you to devote more mental energy, or working memory, to context and making sense of the meaning.

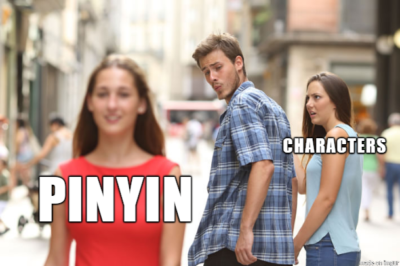

2. Pinyin first, characters second

Research on people learning Chinese as a second language suggests that spending some time focusing on pinyin without characters, and developing some listening comprehension can help learners begin to read Chinese character texts more easily and faster than by trying to learn both at the same time. My own experiences teaching students confirm this finding. In the classroom, when I first focused the student on understanding the word in context and then afterwards focusing on the character, I found students had a smoother process connecting the characters to the sounds and meanings that were already firm in their minds. (I shared that anecdote within an article available here.)

3. Read only familiar words for a while

When you do decide to read text with Chinese characters, find materials that stay within the words you already know when you hear them aloud — no new words! This is helpful for when you are FIRST beginning to read. This helps because it draws on language that has already been introduced and is developing in your head thereby strengthening it with visual representation. Having that nice foundation in the basic language is a great thing! It will prepare you for graded readers at the 300 character level and up. Even when we do begin reading texts with new characters, we want just a little bit, around just 2%, of new vocabulary. See ideas below for ways to get reading material like that — it’s not easy to find when you’re a true beginner!

4.Re-read

Read what you can and then milk it for all its worth. If re-reading as a language learning technique doesn’t sound familiar to you, let me recommend this well-written blog post explaining why and how it helps. If you are a language teacher, you particularly might also want to read another post by the same author, Justin Slocum Bailey, who describes a technique for pre-reading and re-reading in a classroom setting. Here are some re-reading ideas:

- Pick a few highlighters or colored pencils. On the first time reading, highlight words you recognized easily. The second time, use a new color to highlight words you recognize better that time through. On the third pass, highlight words in a third color. (If you have a lot of unhighlighted words after multiple read-throughs, you may want to consider putting that aside for now and find something easier to understand).

- After reading once or twice, change the names of the people in a dialogue to people who interest you, famous or from your own life. Read it again and imagine how those people would react to each other in that dialogue.

- Read again with the names of people you chose inserted but now change the dialogue ever so slightly – swap out a verb or make a negative statement instead of a positive one. The point really isn’t to write, but to make a parallel version of something you already can read so that you can read it again and think about the meaning in a fresh way. If you do this right, it’s not a writing exercise or a drill, but a chance to make a spoof out of your textbook dialogue or at least create a version more meaningful & interesting to you.

- Read it aloud once you have read it silently a few ways. Then, read it aloud in different emotions. Read it like you have a head cold. Read it like you’re a newscaster, your best friend, or your favorite cartoon character. Read it like you just breathed helium. You get the idea: make it fun to read again so that you can process the reading material in a somewhat fresh way.

- If you enjoy drawing, read again, and draw a comic strip version of what happens. Or, use clipart or images you find online for the same purpose.

You certainly do not have to use all of these methods with everything you read. The point is not to memorize a text, but to get the most use out of the limited amount of reading material you can read when you are a beginner. These are simply choices to pick from and there are likely many more creative ways to make re-reading a pleasure!

5. Ping pong reading with a friend.

Do you have another Chinese reader who will read with you? After you read silently on your own, ask your friend to take turns reading a sentence. After they read aloud in Chinese, translate it’s meaning into your language or act out its meaning. Then switch roles; you read the next sentence out loud in Chinese and your partner translates or acts out the meaning. Continue reading going back and forth like this. Some language teachers call this “volleyball reading” but I think it’s more like ping pong reading, since it’s one-on-one. If it’s fun for you, keep score: one point for reading aloud and one point for giving the meaning in your first language. Translation of this type can be useful to confirm your comprehension and is a good skill to have its own right.

6. Ask a friend to write what you can say.

Find a friend who knows Chinese well and can write or type. Sticking only to Chinese you know well, begin to describe a scene or a story. Your Chinese-proficient friend types or writes as you talk. Every so often, pause and read what has been written so far. This is known as The Language Experience Approach. If you are already able to speak Chinese to some degree but do not yet read, it can be a very valuable exercise. The goal is not to type your story as briefly as possible, but to get to see your current vocabulary in print many times. Do not be afraid to repeat some things and include details the best you are able. When you are done, have your friend read the text aloud with you, pointing at each word as it is read aloud. (To me, this sounds like a really great date night with a more proficient Chinese learner or a native speaker, but I might be a geek.) Here I am with a beginning Chinese class doing the same approach, asking them questions to retell a story we made up in class the day before. I typed and expanded on their comments. Here’s a Spanish teacher’s example where he’s hand-writing on a whiteboard.

7. Listen to slow audio while you read along

Find audio materials that coordinate with reading you can understand. Listen to SLOW audio with reading material that includes words you already know by sound. Subtitled audio and video like on FluentU or Yabla may work for you. Audio with transcripts like the Chairman’s Bao, ChinesePod.com, or DuChinese (or a number of other apps) do this, too. For this purpose, I have shared a few videos on YouTube with reading made for my students. Playing videos on slower speeds, pausing and going back, and muting to predict, then listening to check what you read can be useful ways to use subtitled videos. Music videos would work for this too if you have a good understanding of what the lyrics mean. With song, you could even just sing the chorus as it repeats more and often seems simpler than the verses.

Here’s a good one to start: 对不起,我的中文不好 by the band Transition.

8. Read simple books

Find the easiest books that are designed to help you learn to read. These materials intentionally limit the number of vocabulary items, and they intentionally repeat the use of those words — kind of how Dr. Seuss books work. A common mistake is to choose children’s books written for Chinese kids. However, these are not suitable for you because they are not written for you, they are written for Chinese kids who can already understand and speak the language. Think of how a child can understand a book being read to them even though they cannot read it themselves.

Graded readers are recommended instead. These type of story books are designed for those learning Chinese as a second language. These books deliberately include some aids to comprehension and repeated use of vocabulary, such as larger font sizes, word spacing, color, and easily-accessible pinyin (but pinyin that is not placed over the characters).

Sometimes people say that such reading materials don’t “sound natural” because they have simpler language than most native speakers use in real life. Let’s look at it this way: does Dr. Seuss “sound natural”? Perhaps some is not, but such books give English learners simpler, sheltered, scaffolded reading materials that are a lot of fun. And it is real language nonetheless, just simplified using limited vocabulary. Here are some suggestions for beginning level reading materials:

- Books by Terry Waltz: short story books and the chapter book, Susan you mafan

- Books by Haiyun Lu: book series

- Books by Linda Li and Stephen Krashen: Shei hao kan? and Haokan shi bu gou de

- Books by Pu-mei Leng: chapter books

9. Read what you like

Find topics and stories that you enjoy reading about. If you can’t find enough materials that are at your level, you can at least aim for reading things that you find cute, funny, or intriguing in some way, since those will keep your interest longer when it is a bit more challenging. Materials like those can be found in podcasts and apps which organize content by level and list topics in English. This idea of reading what you find more enjoyable is not a new idea, but part of the theory behind free voluntary reading.

10. Re-read what you read last month, semester, year…

Go back and read again things you read a few weeks or a few months ago to realize your progress. Speaking from personal experience, it can be very motivating to realize that you can read faster and easier than you could in the past! Sometimes you may see some words you’ve forgotten. No problem! This re-reading lets you catch them again as you keep stepping towards that 300 character mark, which at that point, the choice of materials you can read really begins to open up.

If you’ve been feeling like there is nowhere to start, now you have some tools and resources to get out there and start reading. You don’t need to stare at pages of Chinese text looking for characters you know like a Chinese version of Where’s Waldo. You can begin to read Chinese right now!